PREVIOUS

Collegium of Supreme Court Judges

September 24 , 2019

2034 days

5088

0

The story so far:

- The recent controversy over the transfer of the Chief Justice of the Madras High Court, Justice Vijaya Kamlesh Tahilramani, to the Meghalaya High Court has once again brought to the fore a long-standing debate on the functioning of the ‘Collegium’ of judges that makes appointments and transfers in the higher judiciary.

- Justice Tahilramani has submitted her resignation after her request for reconsideration of the transfer was rejected by the Collegium headed by the Chief Justice of India (CJI), Ranjan Gogoi, and four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court.

- While sections of the Bar have questioned the transfer as well as the lack of transparency about the exact reason, the Supreme Court (SC) has issued an official statement that the Collegium indeed had cogent reasons and that these could be revealed, if necessary.

Evolution of the Collegium system

- The Collegium of judges is the Supreme Court’s invention.

- It does not figure in the Constitution, which says judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts are appointed by the President and speaks of a process of consultation.

- In effect, it is a system under which judges are appointed by an institution comprising judges.

- After some judges were superseded in the appointment of the Chief Justice of India in the 1970s and attempts made subsequently to effect a mass transfer of High Court judges across the country, there was a perception that the independence of the judiciary was under threat.

- This resulted in a series of cases over the years.

- The ‘First Judges Case’ (1981), or S.P Gupta Vs Union of India case also known as the Judges' Transfer case, ruled that the “consultation” with the CJI in the matter of appointments must be full and effective.

- However, it rejected the idea that the CJI’s opinion, albeit carrying great weight, should have primacy.

- The term “consultation” used in Articles 124 and 217 did not mean concurrence.

- The judgment made the Executive more powerful in the process of appointment of judges of High Courts.

- The Second Judges Case (1993), or Supreme Court Advocates-on Record Association vs Union of India case, introduced the Collegium system, holding that “consultation” really meant “concurrence”.

- It added that it was not the CJI’s individual opinion, but an institutional opinion formed in consultation with the two senior-most judges in the Supreme Court.

- The Supreme Court, in the Third Judges Case (1998), or a Presidential Reference under Article 143 of the Constitution by President K R Narayanan, expanded the Collegium to a five-member body, comprising the CJI and four of his senior-most colleagues.

Members of the Collegium

- The Supreme Court collegium is headed by the CJI comprises four more senior-most judges of the Supreme Court.

- The High Court collegium is led by its Chief Justice of the respective High Court comprises four more senior-most judges of that High Court.

- Names recommended for appointment by a High Court collegium reaches the government only after approval by the CJI and the Supreme Court collegium.

Procedures followed by the Collegium

- The President of India appoints the CJI and the other SC judges.

- As far as the CJI is concerned, the outgoing CJI recommends his successor.

- In practice, it has been strictly by seniority ever since the supersession controversy of the 1970s.

- The Union Law Minister forwards the recommendation to the Prime Minister who, in turn, advises the President.

- For other judges of the top court, the proposal is initiated by the CJI.

- The CJI consults the rest of the Collegium members, as well as the senior-most judge of the court hailing from the High Court to which the recommended person belongs.

- The consultees must record their opinions in writing and it should form part of the file.

- The Collegium sends the recommendation to the Law Minister, who forwards it to the Prime Minister to advise the President.

- Similarly, the Central Government also sends some of its proposed names to the Collegium.

- The Central Government does the fact-checking and investigate the names and resends the file to the Collegium.

- Collegium considers the names or suggestions made by the Central Government and resends the file to the government for final approval.

- If the Collegium resends the same name again then the government has to give its assent to the names.

- But time limit is not fixed to reply. This is the reason that the appointment of judges takes a long time.

- The Chief Justice of High Courts is appointed as per the policy of having Chief Justices from outside the respective States.

- High Court Judges are recommended by a Collegium comprising the CJI and four senior-most judges.

- The proposal, however, is initiated by the Chief Justice of the High Court concerned in consultation with four senior-most colleagues.

- The recommendation is sent to the Chief Minister, who advises the Governor to send the proposal to the Union Law Minister.

Collegium powers on transfers

- The Collegium also recommends the transfer of Chief Justices and other judges of the High Courts.

- Article 222 of the Constitution provides for the transfer of a judge from one High Court to another.

- When a CJ of the High Court is transferred, a replacement must also be simultaneously found for the High Court concerned.

- There can be an acting CJ in a High Court for not more than a month.

- In matters of transfers, the opinion of the CJI “is determinative”, and the consent of the judge concerned is not required.

- However, the CJI should take into account the views of the CJ of the High Court concerned and the views of one or more SC judges who are in a position to do so.

- All transfers must be made in the public interest, that is, “for the betterment of the administration of justice”.

Common criticism against Collegium system

- Some do not believe in full disclosure of reasons for transfers, as it may make lawyers in the destination court chary of the transferred judge.

- Embroilment in public controversies and having relatives practicing in the same High Court could be common reasons for transfers.

- In respect of appointments, there has been an acknowledgment that the “zone of consideration” must be expanded to avoid criticism that many appointees hail from families of retired judges.

- The status of a proposed new memorandum of procedure, to infuse greater accountability, is also unclear.

- Opaqueness and a lack of transparency, and the scope for nepotism are cited often.

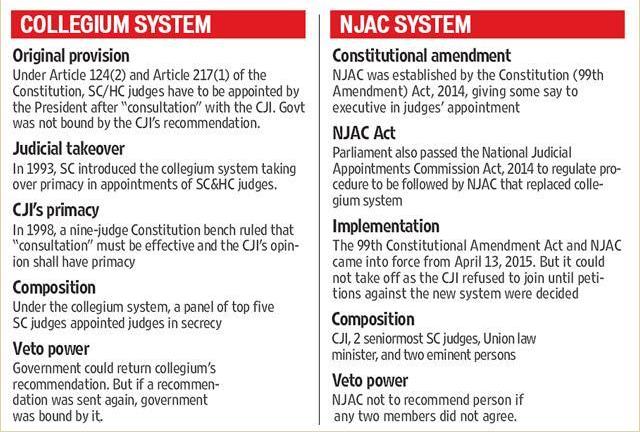

- The attempt made to replace it by a ‘National Judicial Appointments Commission’ was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2015 on the ground that it posed a threat to the independence of the judiciary.

- NJAC would have comprised of the CJI, his two senior-most colleagues, the Law Minister, and two eminent persons, who would be jointly appointed by the Prime Minister, the Leader of the Opposition and the CJI.

- The dissenting judge, Justice J. Chelameswar, termed it “inherently illegal”.

- Even the majority opinions admitted the need for transparency of collegium.

- In an effort to boost transparency, the Collegium’s resolutions are now posted online, but reasons are not given.

Alternative – Memorandum of Procedure

- The judiciary and the government have decided to draft a new Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) to guide future appointments.

- This will address the concerns regarding lack of eligibility criteria and transparency, establishment of a Secretariat and a complaints mechanism.

- But the MoP is still not finalized due to lack of consensus on various matters between the government and the judiciary in this.

óóóóóóóóóó

Leave a Reply

Your Comment is awaiting moderation.