PREVIOUS

LGBTQ+ Rights in India – Part 2

November 19 , 2023

520 days

1027

0

(இதன் தமிழ் வடிவத்திற்கு இங்கே சொடுக்கவும்)

LGBTQ+ Rights in India

Written arguments of Petitioners

- Any social policy is liable to judicial interference if rights are violated.

- The petitioners rely on the rights to equality and non-discrimination as laid out in Articles 14 and 15.

- The Constitution prohibits the state from discriminating based on sex.

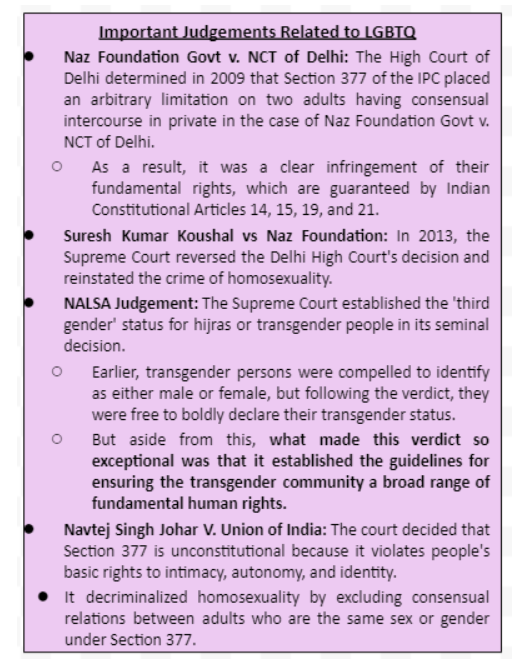

- The word Sex has been interpreted by the Supreme Court in Navtej Singh Johar (2018) to include sexual orientation.

- It granted the right to marry heterosexual couples and not permitting to homosexual couples discriminates on the basis of their sexual orientation.

- Hence, it is following Article 32 of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees the Right to Constitutional Remedies and designates the Supreme Court as the protector of Fundamental Rights.

- The petitioners argued that they are within their rights to approach the Supreme Court.

Equal Rights

-

Same-sex couples should have the same legal rights and protections as opposite-sex couples (under Fundamental Rights to Equality)

Non-recognition of same-sex marriage violates rights

-

Articles 14 (right to equality before the law), Article 15 (right against discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth), Article 19 (freedom of speech and expression), and Article 21 (protection of life and personal liberty) of the Constitution.

Right to life and personal liberty

- Article 21 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to life and personal liberty.

- It includes dignity, privacy, and personal autonomy.

- The Supreme Court recognized the rights guaranteed by Article 21 for sexual and gender minority individuals.

- The Supreme Court held that Article 21 recognizes the right to choose a marital partner in the ruling of Shakti Vahini v. UOI (2018), Lata Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh (2006), Puttaswamy v. UOI (2017), Shafin Jahan v Ashokan K.M. (2018), and Laxmibai Chandaragi B. v. State of Karnataka (2021).

Strengthening Families

-

Marriage provides social and economic benefits to couples and their families, benefiting same-sex individuals as well.

Freedom of expression

- Article 19 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression.

- The Supreme Court held that Article 19 includes full expression of sexual orientation and gender identity.

- The Supreme Court held that the choice of marital partner is an exercise of freedom of expression enshrined in Article 19 in Vikas Yadav v. State of Uttar Pradesh (2016), Asha Ranjan v. State of Bihar (2017), Shakti Vahini v. UOI (2018) and Shafin Jahan v Ashokan K.M. (2018).

Cohabitation as a Fundamental Right

-

Previously, several experts and the Chief Justice of India (CJI) acknowledged that cohabitation is a fundamental right.

-

It is the government’s obligation to legally recognize the social impact of such relationships.

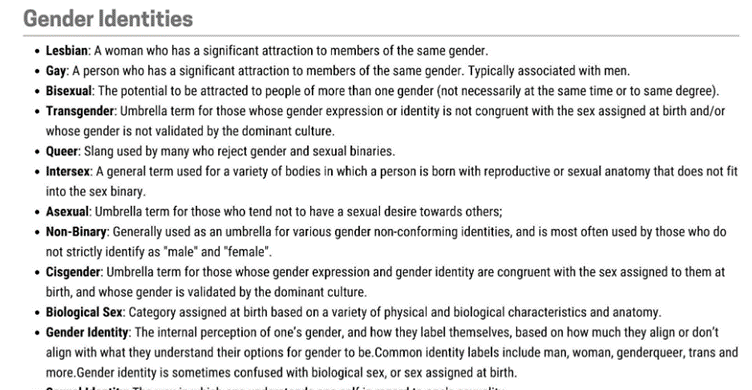

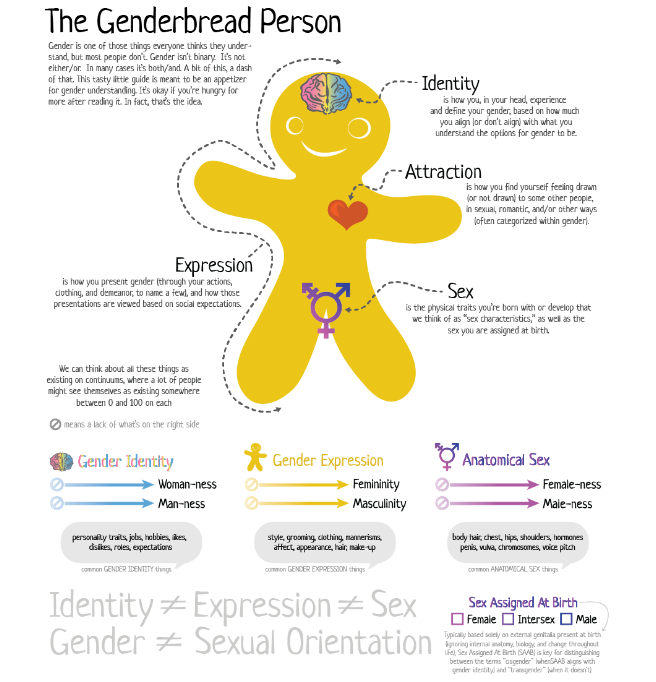

Biological Gender is not ‘Absolute’

-

Since the biological gender is not absolute, and gender recognition is more complex than just one’s genitals.

-

There is no absolute concept of a man or a woman.

Anti-discrimination

- Article 15 of the Indian Constitution guarantees protection from discrimination.

- The Supreme Court extended the protection to include the sexual orientation and gender identity.

- The Supreme Court has recognized the principle of substantive equality in Lt. Col. Nitisha v. UOI (2021).

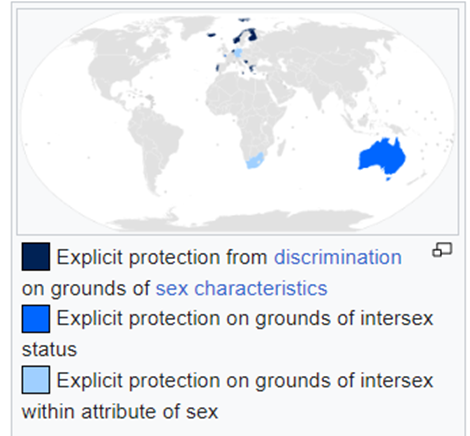

Global Acceptance

-

There are currently 34 countries where same-sex marriage is legal including Australia, Finland, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States of America.

Right to privacy

- Supreme Court recognized this right to be part of the right to life and liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution in the celebrated Puttaswamy (2017) verdict.

Right to marry

- Since the Supreme Court established the fundamental rights of sexual and gender minority individuals in NLSA v. UOI (2014), Puttaswamy v. UOI (2017) and Navtej Singh Johar v. UOI (2018).

- The petitioners argued for extending the right to marry and establish a family to sexual and gender minority individuals based on Articles 14, 15, 19, 21 and 25 of the Indian Constitution.

Violations of decisional autonomy

- The provisions violate the decisional autonomy guaranteed by Article 21 by authorizing any person to object to the marriage.

- The Law Commission published a consultation paper on the Reform of Family Law that recognized the provisions as an impediment to personal autonomy protected by Article 21.

Freedom of conscience and religion

- Article 25 of the Indian Constitution guarantees freedom of conscience and religion.

- Since the Supreme Court ruled that the freedom of conscience of an individual is more than religious beliefs in Puttaswamy v. UOI (2017), the petitioners argued that the freedom to choose a marital partner is an integral component of freedom of conscience.

- Since Hinduism does not prohibit marriage between sexual and gender minority individuals.

International treaties

- India is a party to various international treaties concerning human rights.

- India voted to adopt the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in United Nations General Assembly on 10 December 1948.

- It is enforceable in India under the Protection of Human Rights Act of 1993.

- India ratified the International Convention of Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) on 10 April 1979.

- Over the last three decades, International human rights law has developed an established jurisprudence on the rights to equality, privacy and autonomy of sexual and gender minority individuals and protection from discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Citizenship of sexual and gender minority spouse

- The petitioners argue that the Citizenship Act does not authorize the officials to examine the marriage under Indian law.

- Therefore, as long as the marriage is validly registered overseas and the sexual or gender minority spouse of foreign origin satisfies other conditions, they are entitled to apply for OCI.

Legislative policy

- The petitioners highlighted various entitlements, privileges, obligations and benefits limited to marital, blood or adoptive relationships.

- These legal provisions exclude legally unrecognised spouses and families of sexual and gender minority individuals.

Healthcare

- When a patient cannot communicate their wishes due to being in a persistent vegetative state.

- Having a form of dementia or similar illness, or being under anesthesia, legally unrecognised spouses and families of sexual and gender minority individuals are not allowed to make healthcare decisions for them.

- Legally unrecognised spouses and families of sexual and gender minority individuals face discrimination in organ donation in the case of both living or deceased partners.

- Under the Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act of 1994, the declaration to donate organs requires the presence of at least one marital, blood or adoptive relative.

- Sexual and gender minority partners need prior approval of the Authorization Committee under the Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act.

Finance

- Sexual and gender minority family members lack the rights around succession, maintenance, joint ownership of assets, taxation and benefits.

- As private entitlements exclude sexual and gender minority family members, sexual and gender minority individuals face more barriers and higher scrutiny in privately offered life insurance nominations, owning joint bank accounts and lockers, and mutual funds and savings plans.

- According to the Income Tax Act of 1961, the payments made on behalf of a spouse are included in the deduction when computing the total income.

- Sexual and gender minority family members cannot claim such deductions.

- According to the Supreme Court ruling on Rajesh v. Rajbir Singh, the spousal consortium considered in the claims, including the claims for injury and death in the Motor Vehicle Act of 1988 cases, is only available to married couples.

- Hence the legally unrecognised spouses of sexual and gender minority individuals are denied such claims.

Leave a Reply

Your Comment is awaiting moderation.